A couple of weeks ago a young moose moseyed into the front yard and helped himself to the fallen fruit from an apple tree.

Onlookers were delighted – but not surprised. At Mount St. Francis (Cochrane, Alberta), near the foothills of the Canadian Rockies, humans are treated to more than sweeping vistas of the Big Hill Creek Valley. They come to this Christian retreat center in southern Alberta expecting to get away from it all. Here they find serenity, 500 acres where the prairie ends, plenty of space for soul-searching. But they also find a spirit of harmony, the peaceful co-existence of people with the land and with God’s creatures, occasional guests like moose, foxes and cougars. It doesn’t get more Franciscan than that.

For 70 years this has been one of Alberta’s treasures – and one of its best-kept secrets.

“It’s not just the view,” says Susan Campbell, Director of the retreat center since 2015 and formerly with the Pastoral Centre for the Diocese of Prince George in British Columbia. “People say there’s a spirit here of hospitality and simplicity.” But there’s also a conundrum. “Our calendar is booked” with retreats for men’s and women’s groups, Secular Franciscans and school groups. “There are things we advertise that are well-known in the community,” like the October blessing of animals and a popular Christmas pageant. “But we would like for people to know our ministry and attend our workshops.”

The mantra of Mount St. Francis is, “peace, healing and prayer”. They host a half-dozen programs a year for people recovering from addiction to alcohol. Because the wide open spaces invite introspection, “The big thing here is silence,” says Kevin Lynch, one of the eight Franciscans of Holy Spirit Province who live in the adjacent friary. “People come here to pray.”

Slow down

It’s hard to imagine that anyone could leave here feeling stressed. Right off the lobby is a long wall of windows facing west, toward the mountains, with a row of recliners lined up alongside, like deck chairs on an ocean liner.

Trails mowed through prairie grass lead past panoramic scenery and through woods to a log cabin hermitage. Docile draft horses grazing in the neighboring field poke their noses through a fenced enclosure for treats. To the south of the center, perched on a hill that is considered sacred, is one of two sets of Stations of the Cross on the property.

It has always been holy ground, Susan says, from the time the First Nations people known as the Stoney Indians came here to hunt. They called the elevation that overlooks the retreat house “Manachaban”, or the Big Hill. The core of the complex is a sandstone house built by a Canadian politician, Charles Wellington Fisher, in 1908.

In 1949 Franciscan friars bought some of the property, received the rest through a donation and added a wing for retreatants. They opened on Aug. 15, 1949, with a program for clergy from the Diocese of Calgary. That fall when they mounted their first retreat for lay people, one of the teen-age guests was Louis Geelan, who became a friar and is now part of the retreat team.

Time to unwind

They envisioned an ecumenical oasis off the beaten path. A signpost on the gravel road that leads here says, “Shalom”.

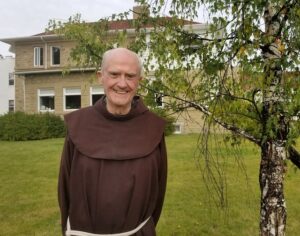

“All are welcome in the name of Christ,” says Kevin, the peripatetic guardian of the friary and the face of Franciscan hospitality for many who visit. “People on the edge of the Church come here,” as well as Buddhists and meditation groups. “We are the liminal church. People come here and dump their stuff and it stays here.”

In some respects, business is booming. Weekends are booked solid. The way they run lay retreats, using a system of “Captains” to register guests, gives staff members like Susan the leeway to organize and guide some of the other programs. Although Mount St. Francis has welcomed the world – Provincial Ministers of the English Speaking Conference have met here, and last week they hosted ESC communicators – a lot of folks still don’t know it exists.

These are challenging times for retreat houses. The crazy busy-ness of modern life and the distractions of technology make getaways more difficult. Loyal supporters help maintain the Mount, but the wish list extends far beyond basics. “We need a new building” to replace the complex built around the original sandstone structure, Kevin says – not an easy wish to fulfill.

The friars and the staff know this place is special. Guests get something rare: a chance to hit “pause” – time to breathe and the space to reflect in surroundings that celebrate the glory of God. Where else can you get such a view?

And if you’re lucky, you might see a moose munching an apple.

Toni Cashnelli

(Communications Director for the Franciscan Friars of the Province of St. John the Baptist in Cincinnati, Ohio)